Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 is a classification system for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions a firm is creating through its operations, energy usage, and the wider value chain. This categorisation was first introduced in the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, along the system for accounting and reporting corporate GHG emissions1. The GHGs included in the framework are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFC), perfluorocarbons (PFC), sulphur hexafluoride (SP6), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)2.

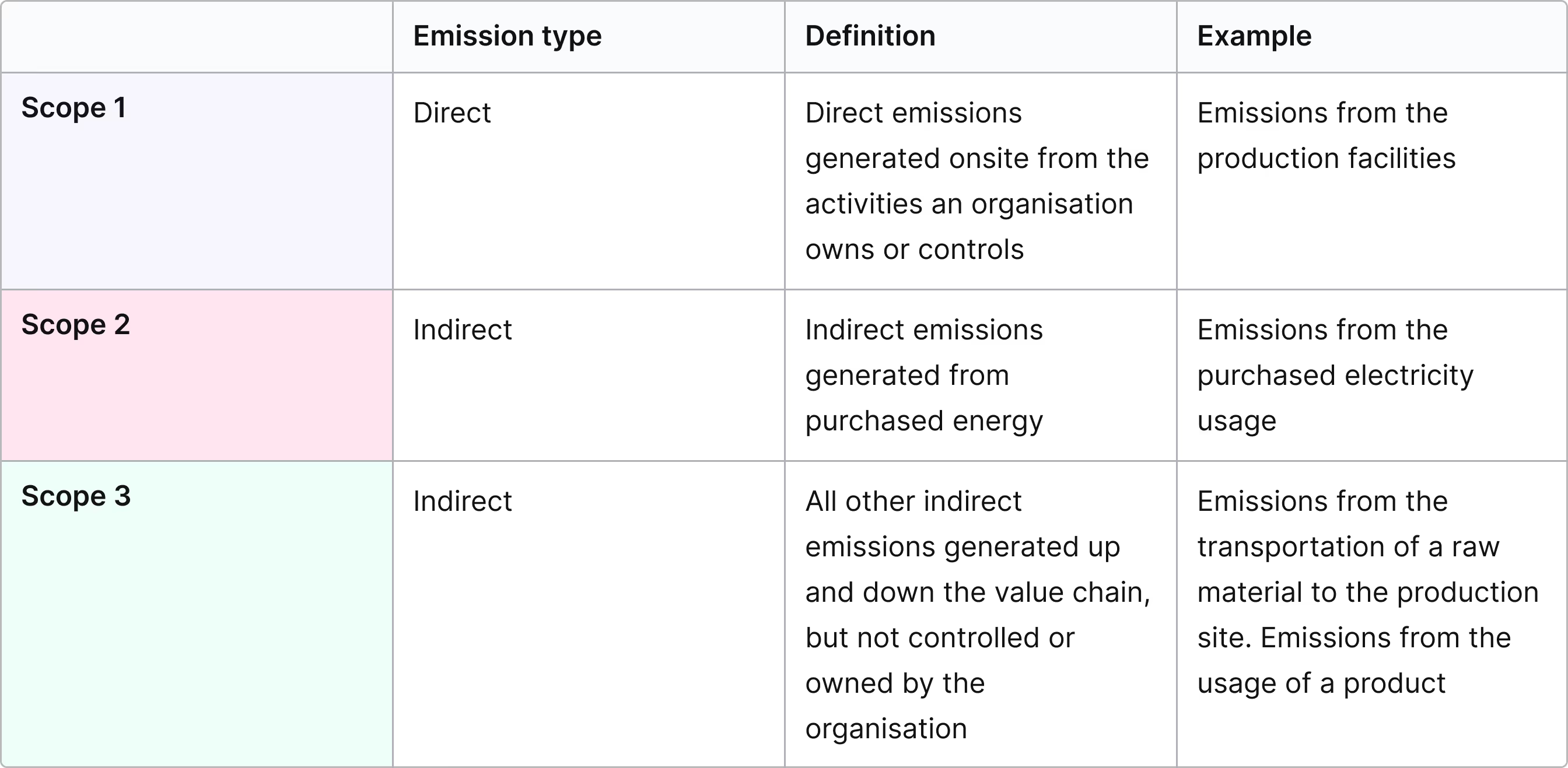

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol classifies emissions based on where they originated from. Scope 1 emissions are defined as emissions generated onsite from the activities an organisation owns or controls. Scope 2 category includes indirect emissions generated from purchased energy. Scope 3 emissions are all those emissions a firm is responsible for but which happen outside of its walls and are controlled by other parties up and down the value chain.

The GHG Protocol includes complementary standards for diverse scopes (corporate, product, and project) and applications (emissions mitigation, policy action, and others)3. Two of the key standards are the Product Standard and the Corporate Standard, which will be the focus of this article. Even though these are independent guidelines, when taken together, they enable firms to create a full picture of corporate emissions: the lifecycle emissions of each of a company’s products with additional Scope 3 categories.

Along with its many benefits, the GHG Protocol plays a vital role in corporate efforts to tackle climate change. The knowledge of Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions provides companies with tools to strategically reduce environmental pollution by understanding where it originates from in the first place.

To utilise these benefits, a system for GHG emissions accounting should be set up, which is a demanding undertaking, especially when talking about Scope 3. Scope 3 emissions calculation requires wide-scale collaboration along the value chain raising concerns around inaccessibility of information, confidentiality, alignment, and scalability.

This article sets out to make a comprehensive overview of the Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions using an example of a plastic resin producer and a car manufacturer. It also suggests a solution for efficiently collecting primary data for Scope 3 emissions accounting. In particular, the following will be discussed:

- What are Scope 1 emissions?

- What are Scope 2 emissions?

- What are Scope 3 emissions?

- What is the difference between Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions?

- Why is it important to know your Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions?

- Challenges of Scope 3 emissions accounting and reporting

- How Circularise can help with reporting Scope 3 GHG emissions?

Scope 1 emissions explained

What are scope 1 emissions?

Scope 1 are all direct emissions generated onsite from the activities an organisation owns or controls1.

What are examples of Scope 1 emissions?

How to read examples?

The examples will vary depending on the choice of scope and boundaries for the purpose of accounting4 and legal structures1. For all the examples in this article however, the following assumptions are made. A plastics producer owns and controls only the activities related to the manufacturing of plastic resin, excluding the petrochemical production, while a car brand controls only the activities related to the car parts manufacturing and assembling process (other production processes are outsourced to the supply chain partners).

Example of a company producing plastic resin

For plastic resin, Scope 1 emissions include those GHG generated in the facilities of a plastics producer where resin is manufactured from the raw material

Example of a company manufacturing cars

In the case of a car, Scope 1 includes emissions that are generated by the manufacturing of an engine or a mainframe from aluminium, zinc, and other minerals, as well as its assembly into a final product on a company’s production line.

What are Scope 1 emissions categories?

Scope 1 includes emissions from:

- Manufacture and processing of chemicals and materials (e.g. waste, aluminium, adipic acid, ammonia manufacture)

- Company owned fuel use resulting in the generation of electricity, heat, or steam on site (e.g. in boilers, furnaces, turbines)

- Transportation and use of controlled vehicles (e.g. trucks, trains, ships, aeroplanes, buses, cars)

- Leaks and other irregular releases of gases or vapours known as fugitive emissions (e.g. equipment leaks from joints, seals, packing, gaskets; methane emissions from coal mines and venting; hydrofluorocarbon emissions during the use of refrigeration and air conditioning equipment; methane leakages from gas plants and pipelines)

What is the difference between the Scope 1 product lifecycle emissions and corporate emissions?

When looking at a lifecycle emissions of a single product, only activities necessary to produce the selected item are taken into account, contrary to assessing all the production processes at a site4.

Scope 2 emissions explained

What are Scope 2 emissions?

Scope 2 GHGs are indirect emissions generated from purchased energy1. These emissions are caused by the reporting company, but are not directly under its influence. The emissions physically occur at the facility where energy is produced and hence are owned and controlled by a firm.

What are examples of Scope 2 emissions?

Example of a company producing plastic resin

Scope 2 emissions for a plastics producer are GHGs from the use of purchased electricity, heating, and cooling used on site during the production of plastic resin.

Example of a company manufacturing cars

In the example of a car, Scope 2 emissions are GHGs created from the usage of the electricity supplied by an energy company to the facility where the car is assembled.

What are Scope 2 emissions categories?

Scope 2 includes emissions from5:

- Purchased electricity

- Purchased heating and cooling

- Purchased steam

What is the difference between the Scope 2 product lifecycle emissions and corporate emissions?

When looking uniquely at a product, only emissions from the purchased energy necessary to produce the selected item are calculated. On the other side, the heating and cooling of offices is part of corporate emissions.

Scope 3 emissions explained

What are Scope 3 emissions?

Scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions generated up and down the value chain, but not controlled or owned by the organisation.

What are examples of Scope 3 emissions?

Example of a company producing plastic resin

For plastic resin, Scope 3 emissions are generated by the upstream primary petrochemical production, as well as the delivery of the raw material to the site of the plastics producer. On the downstream side, Scope 3 originates from the melting and moulding of plastic resin into a final plastic product and its retail, consumption, and end-of-life. The plastic producer does not know what their resin will become (e.g., toy or food container) and where it will end up at (e.g. incinerated, put in a landfill, or recycled).

Example of a company manufacturing cars

An example of Scope 3 emissions for car manufacturing are GHGs generated from the upstream sourcing of materials - such as aluminium, zinc, plastic, rubber, and others. Scope 3 also includes the delivery of the engine and other parts to the site of the car manufacturer (which is an upstream activity) and the use of the car by a consumer and the end-of-life (which are downstream activities). The company is not aware how their car is going to be disposed (e.g. incinerated, put in a landfill, or recycled).

What are Scope 3 emissions categories?

Scope 3 includes emissions up and down the value chain from6:

- Extraction, production, and transportation of purchased goods and services. This category includes emissions not otherwise incorporated in other categories of activities mentioned below

- Extraction, production, and transportation of capital goods - items used by a firm to produce the final good or service (e.g. machinery, building, facilities)

- Fuel- and energy-related activities outside of Scope 1 and 2 (e.g. emissions from activities upstream of a company’s fuel and electricity provider)

- Transportation and distribution of products between a company’s suppliers, its own operations, and the end consumer

- Disposal and treatment of the waste generated in use and operations

- Business travel when employees travel for work in vehicles not owned or controlled by a firm

- Employee commuting when employees travel to the office from home by car, bus, metro, and other means of transportation

- Operating leased assets that were leased by the reporting company (lessee) or that were owned and leased to other entities by the firm (lessor)

- Processing of sold products

- Use of sold products

- End-of-life treatment and waste disposal of sold products

- Operation of franchises

- Operation of investments, including equity and debt investments and project finance

What is the difference between the Scope 3 product lifecycle emissions and corporate emissions?

Not all these activities are included in Scope 3 when looking at a single product’s emissions. For example, operations of franchises and investments, employee commuting, and business travel are not accounted for. However, with a product lifecycle focus, the following emissions-generating activities stay relevant4:

- Material acquisition

- Pre-processing

- Distribution and storage

- Use

- End-of-life

What is the difference between Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions?

Scope 1 and 2 emissions are within the control of an organisation and focused on operation and energy consumption owned and controlled by its management team6. Scope 3 includes those emissions a firm is responsible for but which happen outside of its walls and are controlled by other parties. To calculate a total footprint, Scope 1 and 2 are not sufficient. Scope 3 is most impactful as it often accounts for up to 85-95% of a company’s emissions7.

Even though it might be challenging to figure a way around the emission categories, once it is done, the medium and long-term benefits of GHG accounting are significant.

Why is it important to know your Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions?

GHG accounting presents a growth opportunity. It enables firms to monetise sustainability efforts, increase consumers’ willingness to pay, and attract green investments. Knowledge of a company's emissions improves the decision-making and product design, ensures compliance with sustainability regulations, and contributes to the preservation of a healthy planet.

Financial incentive

Capture green growth

Once made public, GHG reports enable firms to capture green growth. McKinsey & Company observes that, across various industries, if priced right, companies can benefit from premiums on sustainability8. A prime example of this trend is the chemicals industry, where firms with more low-carbon, biological, or recyclable products deliver higher total returns to shareholders9.

Increase consumers’ willingness to pay

Furthermore, GHG reports demonstrate sustainability efforts to stakeholders, investors, and consumers1. A study by Accenture has found that while consumers remain primarily focused on quality and price, 83% of them think it is extremely important for companies to design products to be reused or recycled. Similarly, two-thirds of consumers are willing to pay extra for sustainable products. Learn how to make reliable sustainability claims here.

Attract green investments

Increased willingness to pay, promising future cash flows, and financial performance also attract investors12. Nowadays, many investment portfolios include sustainability goals9. Hence, by not demonstrating tangible efforts, firms risk losing investments due to investor protection.

Manage risks

By measuring emissions in the value chain, a firm can better identify and prepare for risks from supply chain disruptions and price volatility such as resource scarcity, market failures, and natural disasters1. Furthermore, it can help a company avoid threats associated with stakeholder or regulatory pressures, decreasing demands for polluting products, and asset devaluation9.

Allocate resources better and design greener products

Similarly, increased visibility of emissions enables to track where and how the resources are used and, consequently, better allocate them to reduce product emissions4 or costs9. For example, knowing which activities generate most emissions, a firm can strategically reduce energy costs by installing an efficient cogeneration plant on the most energy-inefficient site (for Scope 1 activities) or switching to less GHG intensive sources of electricity (for Scope 2 activities). Information on emission can also be used to improve the product design13. For example, by reducing the material use or by switching from fossil-based materials to bio or circular.

Regulatory incentive

Comply with new regulations and circumvent sanctions

Understanding Scope 1, 2, and 3 GHG emissions is necessary to comply with existing and upcoming sustainability regulations breaking which leads to sanctions ranging from public statements to fines.

One of such regulations is the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) proposal which forces firms to annually report on their Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, along with other disclosure requirements. Non-compliance can potentially lead to fines of € 10M, 5% of the annual turnover, or twice the amount of the profits gained/losses avoided because of the breach.

Another example of a sustainability regulation that encourages GHG accounting is the German Supply Chain Act. It requires firms to conduct human rights and environmental impact due diligence across their supply and value chain, including indirect suppliers (Scope 3). If a company is found to be non-compliant with this regulation, it can be fined up to 2% of annual revenue.

Read more about the aim, scope, timeline, and disclosure requirements of the CSRD and the German Supply Chain Act.

There has also been an array of financial regulations enhancing green investments. For example, the Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR) forces investors to share how they account for the effects of their investments on people and the environment15.

Moral incentive

Sustain a decent quality of life for all

Future of the planet and humankind depends on the decisions made by us, including the leadership teams. Preserving a livable planet is impossible without corporate commitments. Knowledge of Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions provides companies with insights about where the emissions originated from which are required to effectively reduce environmental pollution. Moreover, GHG accounting offers a chance to gradually decrease emissions by indicating which activities are most emission-heavy. Hence, setting up a Scope 1, 2, and 3 reporting system is an important first step in corporate efforts to slow down climate change.

How to calculate Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions according to the GHG Protocol?

To report and account GHG emissions, follow these 8 steps16:

- Define business goals

- Review accounting and reporting principles

- Set the scope and boundaries

- Collect data from your sources (best case scenario) and, if needed, use publicly available secondary databases to compensate for the gaps (least desirable scenario)

- Allocate emissions and removals

- Set a target and track emissions over time

- Consider assuring emissions

- Report emissions

For more detailed instructions, check the guidance documents, calculation tools, and online training materials that explain how to adopt and measure GHG standards in specific industries or in more complex cases.

However, even with all these tools, the reporting of Scope 3 emissions is not an easy undertaking.

Challenges of Scope 3 emissions accounting and reporting

Key challenges of Scope 3 emissions accounting are associated with inaccessibility of information, confidentiality concerns, need for alignment with diverse suppliers, and unscalability.

- First, a vast majority of organisations only have access to their direct suppliers, while Scope 3 emissions calculation requires wide-scale data exchange between various value chain actors, including consumers. For example, when calculating downstream emissions, a plastic resin producer is not aware what their product will become (a toy or a food container) and where it will finally end up (incinerated, recycled, or other).

- Second, the need for data exchange raises concerns about trust, confidentiality, and privacy. This issue is most prominent for the upstream supply chain actors who have to maintain trade secrets.

- Third, the alignment on Scope 3 interventions, terminology, and sustainability metrics between supply chain partners takes time.

- Finally, the data management systems are usually either non-existent or unscalable, with information required for GHG accounting often being shared manually through numerous files, surveys, and emails. Establishing such systems might be time-consuming and expensive.

At the same time, knowing the upstream and downstream emissions is essential to calculating and reducing a company’s negative impacts because as much as 85-95% of corporate GHGs originate in the value chain7. So, how can a firm collect the primary data efficiently?

How Circularise can help with reporting Scope 3 GHG emissions?

Circularise addresses some of these key challenges. It offers a blockchain-powered supply chain transparency software, that allows companies to trace products across supply chains and reliably share key insight into their products with other actors down and up the value chain, without risking sensitive data.

Circularise’s software enables firms to create Digital Product Passports, which then flow through the supply chain with the physical goods. Key information, including emissions, is added to the passports at each step. Companies, in turn, can use our patent-pending Smart Questioning technology to share insights into sustainability and other product aspects with brands, regulators, and consumers while keeping their sensitive data completely private and secure.

Hence, Circulairse’s Digital Product Passport enables firms to access indirect suppliers to track product emissions on a large scale and over time and to generate product life cycle emission reports that can be integrated into corporate accounts.

The tool is supply chain agnostic and can be applied to various industries and products, as well as other environmental metrics.

Read the case studies on how Circularise achieved visibility for the automotive supply chain here and for the plastics value chain here.

Source: Circularise.

Contact us to discuss the implementation of Digital Product Passports and how to securely share data with members of your value chain.

Circularise is the leading software platform that provides end-to-end traceability for complex industrial supply chains. We offer two traceability solutions: MassBalancer to automate mass balance bookkeeping and Digital Product Passports for end-to-end batch traceability.

.png)