The mass balance approach is a well-established chain of custody model that emerges as a promising path to advancing circularity. Already implemented in various industries with complex supply chains, the mass balance approach is favoured thanks to its flexibility and scalability. As such, the technicalities of mass balancing have rapidly become an important topic in the sustainability dialogue, especially in the plastics and petrochemical industry.

As Europe's third-largest CO2 emitter due to its reliance on fossil fuel use, the plastics industry plays a significant part in the EU's efforts to cut emissions. With governments and companies striving to boost plastic recycling and the uptake of recycled materials, mass balancing in the plastics industry has become particularly important due to the complexity of plastic recycling processes.

While mechanical recycling is well-established and commercially viable for certain applications, it is also limited by regulatory, technical, and economic challenges. Chemical recycling complements mechanical recycling, processing otherwise unsuitable plastics that are contaminated or too degraded. This boosts overall recycling rates, offering alternative ways to convert waste into high quality plastics and keep polymers that are difficult to recycle in the loop. In this way, the industry can significantly reduce the reliance on new fossil resources, driving progress towards a more sustainable and circular plastics industry.

However, creating products with recycled content poses significant challenges for sustainability claims. Certain mass balance methods allow companies to claim the use of recycled content in a flexible and scalable way. The lack of standardisation around mass balance accounting and certification has sparked a debate on the accuracy of product content claims and a growing concern over the increased risk of greenwashing.

This article delves into the various mass balance accounting methods, examines how each method assigns recycled content to the final product, presents the debate over these methods and their implications, and looks at what is in store for mass balancing in the plastics industry.

What are the different models of mass balance accounting?

Allocation is the process of assigning the proportion of sustainable inputs (or feedstock) to specific outputs (or products). In other words, it determines how to account for the sustainability claims of products.

This involves meticulous chain-of-custody accounting of the different mass balance methodologies to distinguish between virgin, bio-based, and recycled plastics throughout the supply chain. Establishing harmonised standards and rules for allocation is crucial for upholding market confidence in the accountability of mass balance systems.

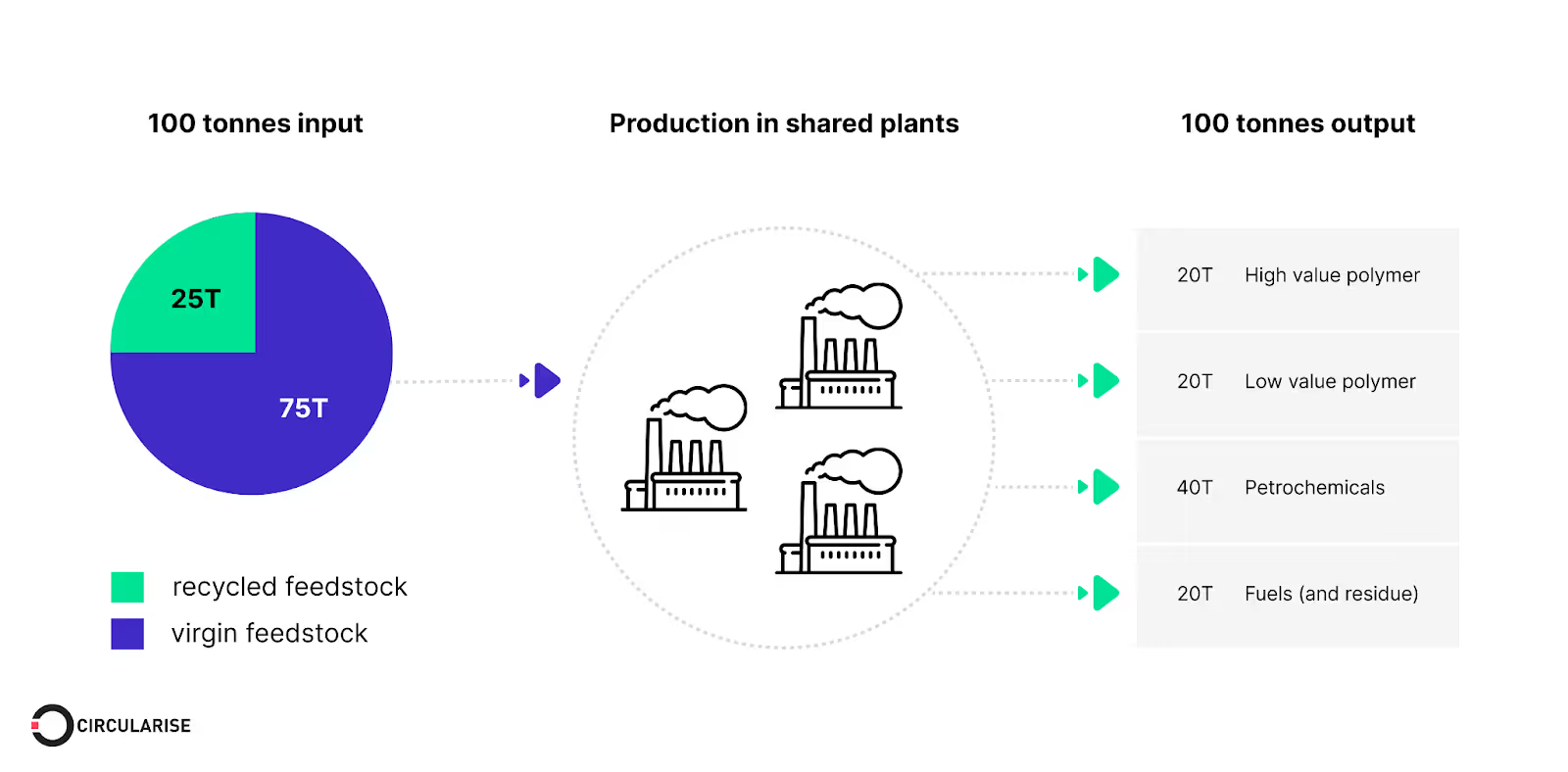

Consider this simplified example: 25 tonnes of recycled feedstock is mixed with 75 tonnes of virgin feedstock. Assuming identical mass across all materials and no mass loss in the processes, the blended feedstock produces 100 tonnes of the following various outputs:

- 20 tonnes of high value polymer

- 20 tonnes of low value polymer

- 40 tonnes of petrochemicals

- 20 tonnes of fuels

Let’s examine how the three common mass balancing models in chemical recycling, each defined by its own set of rules around attribution and reattribution, can go on to make different sustainability claims about their products.

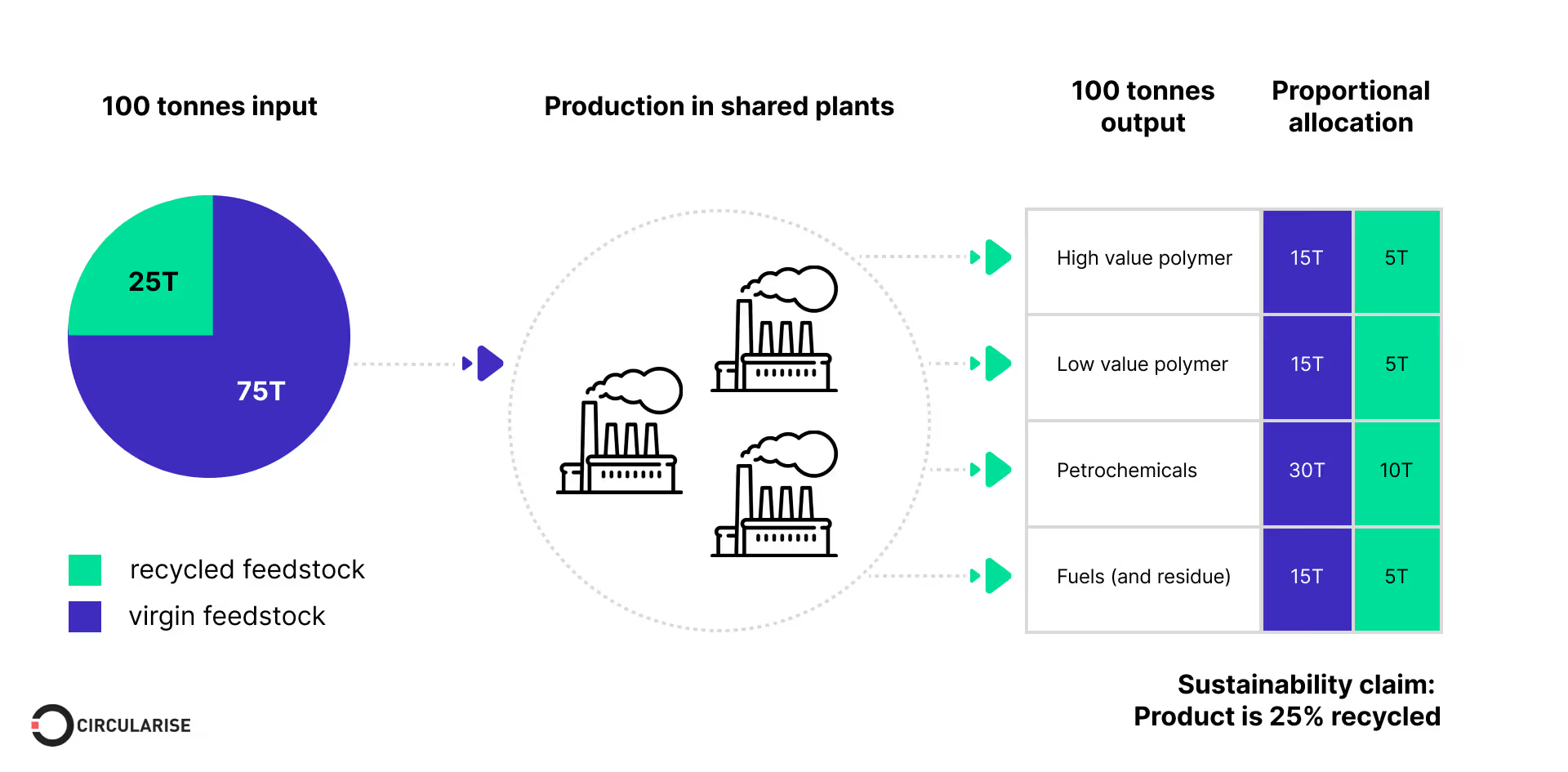

Proportional allocation in mass balance accounting

Proportional allocation in mass balance accounting is where the output is divided according to the proportion of different types of input. This method is based on the principle that the distribution of outputs should directly reflect the proportion of the various inputs.

Based on the example, all outputs under this method would claim to have 25% recycled content. This method assigns the same ratio of recycled content ratio in the feedstock to all outputs, including energy, fuel, polymers, petrochemicals, and residues. Reallocation of attributed recycled content between different outputs or across production sites is prohibited, making this the least flexible, but most accurate method.

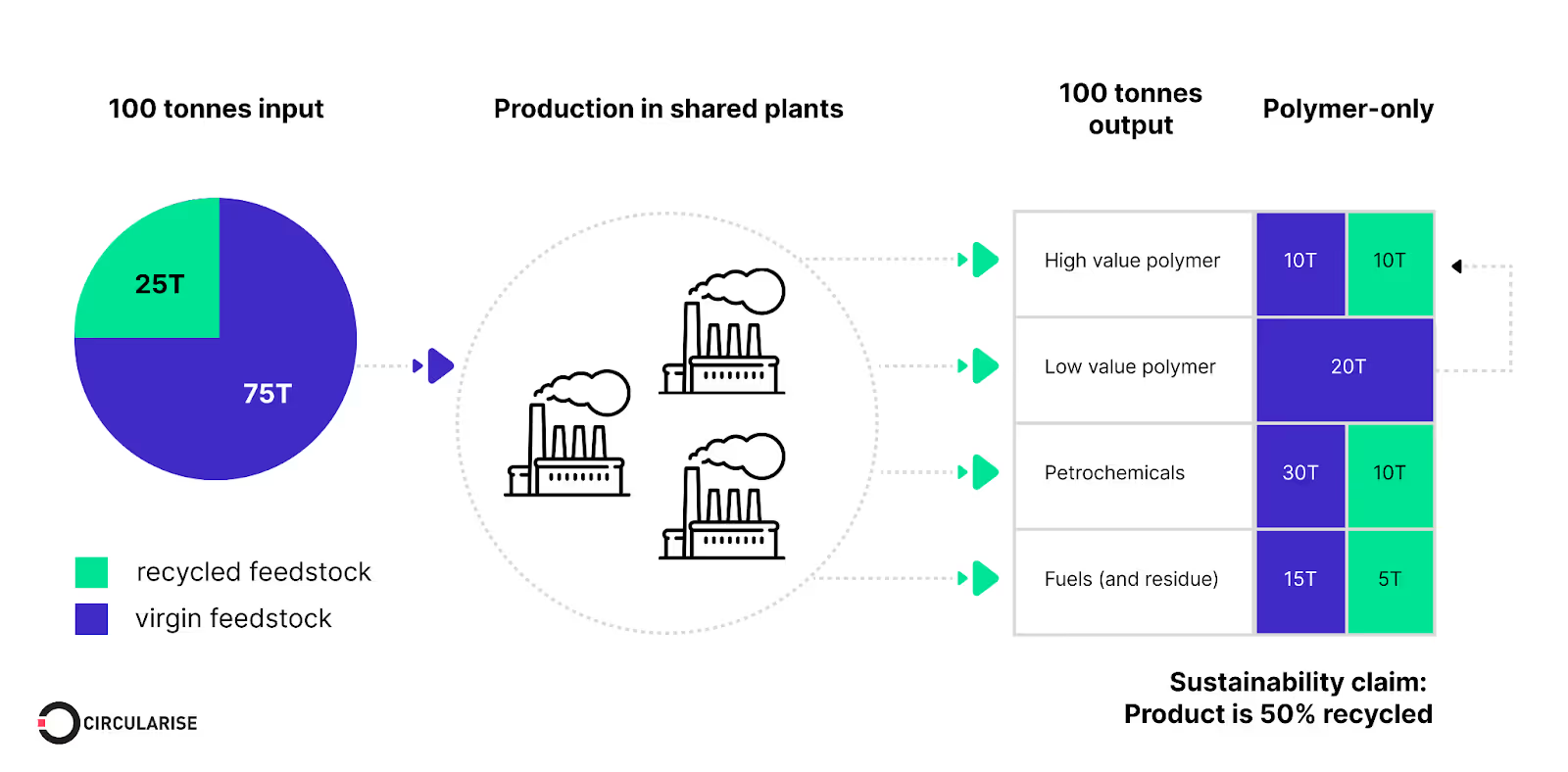

Non-proportional allocation in mass balance accounting: Polymer only

In this polymer only allocation method, recycled polymer content can only be allocated to the production of other polymers. Any non-polymer outputs or products are lost and cannot be applied to other products. This makes it more flexible than the proportional allocation mass balancing, but more restrictive than the fuel exempt method.

Going back to the example, manufacturers are able claim 50% recycled content for their high value polymer product. This method allows the assigning of recycled content in the low value polymer output to the high value polymer output. Reallocation of recycled content from petrochemicals and fuels is not allowed, making this more flexible than the proportional allocation method.

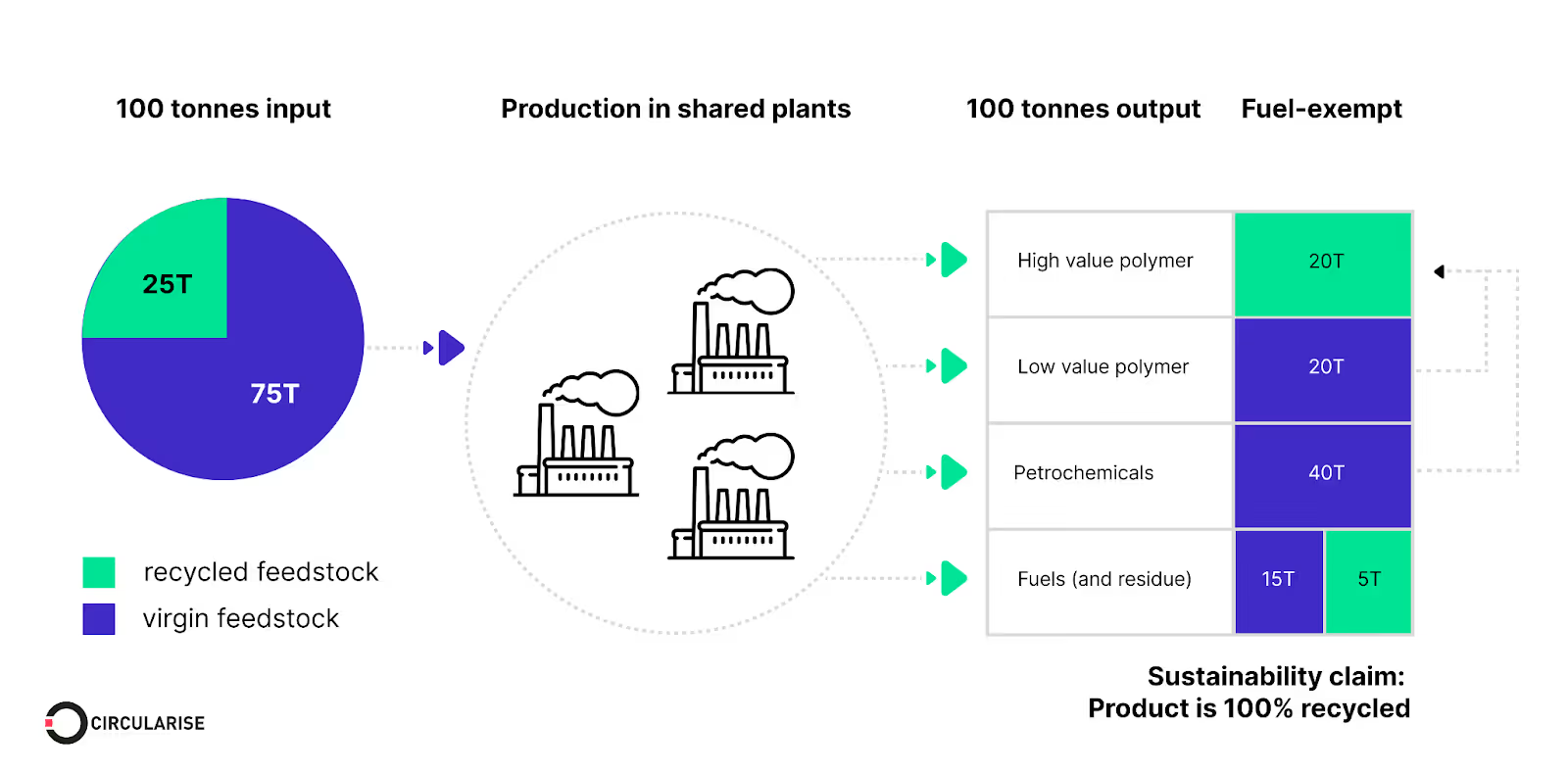

Non-proportional allocation in mass balance accounting: Fuel exempt or fuel-excluded

The fuel exempt allocatoin method of mass balancing allows the transfer of recycled content credits between co-products, which effectively increases the declared ratio of recycled content in co-products. In this situation, however, the fuel outputs are not considered recycled materials and are excluded from mass balance calculations. Any portion sold or consumed as fuel cannot be allocated to another co-product and is treated as system losses.1

With this method, manufacturers are able to claim 100% recycled content for their high value polymer products. This method allows for the reallocation of recycled content from the low value polymer and petrochemical outputs to the high value polymer output.

The fuel exempt method does not allow the transfer of recycled credit from fuels to a product, a move that is allowed under free allocation. This motivates companies to focus on the production of non-fuel items that stay in the production loop rather than being used for energy. This flexibility makes it easy for companies with large-scale operations to adopt this method.

Free allocation in mass balance accounting

Certain standards permit the free allocation approach in mass balance accounting, where recycled content from the input feedstock can be freely attributed across different co-products resulting from a single process. While free allocation offers the most flexibility and market advantages, it requires careful management to avoid the pitfalls of greenwashing as the declared recycled content of a product would not match the precise amounts in each product.

What is the debate around mass balance accounting?

Consumers and consumer brands want product claims to accurately reflect what the product is made of, but this gets complicated with mass balancing. The mass balance debate focuses on whether the EU should implement the fuel exempt mass balance standards for chemical recycling as it impacts product sustainability claims.2

As the EU’s Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) on Waste discussed the methods for determining the recycled content in plastics using mass balance methods, they faced strong resistance to the adoption of the fuel exempt mass balance method.

There was division even within the plastics industry. Some groups feared this could potentially prevent a level playing field between mechanically recycled plastics, usually tracked in segregation, while chemically recycled plastics are mass balanced.3 Others believed the fuel exempt method would undermine the credibility of recycling claims and disincentivise sustainable practices.4 The European Waste Management Association (FEAD) took the official stance that the polymers-only method is the best compromise for a sustainable recycling sector.5

At the same time, environmental groups, like Zero Waste Europe, raised concerns about the fuel exempt mass balance approach, flagging an increased risk of misleading sustainability claims or greenwashing. They call for stricter, more transparent standards to ensure that recycling claims reflect tangible environmental benefits and contribute to real waste reduction and carbon emissions improvement.6

Amidst this controversy, twenty associations in the plastics supply chain lobbied EU Member States to agree on using a harmonised mass balance method that allows fuel use exemption. With the EU's recycling rate at 38% and a goal of reaching 50% by 2025, chemical recycling is needed to achieve recycling objectives.7

Products that lack a substantial percentage of sustainable feedstock fail to attract commercial interest. Fuel exempt mass balance finds a middle ground amid the spectrum of rigid and lax regulations, permitting some flexibility for companies in attributing recycled content. This allows companies to significantly increase plastic recycling rates and the use of recycled feedstock.

At the time of publication, the European Parliament's plenary session rejected the motion objecting to the fuel exempt mass balance method.8 In other words, fuel exempt mass balance accounting remains a valid option within the EU’s recycling framework.

Recommendations for the future of mass balancing

To advance recycling, there must be an environment conducive to investment and a neutral stance toward emerging technologies and methodologies. From a broader perspective, mass balancing serves as a viable transitional step to boost the amount of sustainable or recycled feedstock in production. With more consumers willing to pay a premium for sustainable products, there is a positive economic effect on the value chain. Material manufacturers can market their 100% recycled materials, which are mass balanced, at higher prices to plastic converters and brands, and direct profits towards sustainability initiatives.

However, the present scope of certification schemes and regulations is primarily focused on tracking certified materials. This could potentially overlook accurate allocation and accounting of emissions downstream for co-products. Where there is free allocation or fuel exempt mass balancing, the flow and reported impacts of co-products are not as rigorously tracked or confirmed after they leave the production site. In such cases, the problem of double counting can arise when using primary data to calculate Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) or Product Carbon Footprints (PCFs) for uncertified co-products.

Double counting in mass balance refers to the inaccurate reporting or accounting of the same quantity of recycled content or emission reductions more than once along the supply chain. This can happen when recycled inputs and environmental benefits are allocated across multiple products without proper accounting.

Hence, it is recommended for the industry to carefully allocate both material credits and emissions appropriately so that data shared downstream for co-products reflects mass-balance accounting to avert double counting. We also recommend certification schemes and regulators consider taking a systems perspective on tracing material credit and emissions balance across supply chains, and discourage double counting by providing data & calculation guidance for co-products, their traceability and verification.

The future of mass balancing

As the world grapples with the challenges of waste management and resource conservation, the need for accurate material tracking and accounting will only grow. While mass balancing isn’t perfect, it is a practical step forward in achieving material segregation and traceability. Transparent communication with consumers is important as it enables them to make informed choices aligned with their values, and can help mitigate the negative consequences of greenwashing.

Despite criticisms, mass balancing remains critical for enhancing recycling processes to meet sustainability objectives. However, the risk of double counting needs to be addressed to uphold the credibility of sustainability claims. Third-party certifications like RED II biofuels and ISCC PLUS play a crucial role in reinforcing the trustworthiness and integrity of sustainability claims. Coordinated effort is key for the future of mass balance in a sustainable recycling future.

On the path towards a circular economy, it's clear that flexible solutions and continued investment in recycling innovation are crucial. Each step toward greater sustainability plays a part in moving us towards a more sustainable and resilient future. Regardless of the mass balance allocation method your company utilises, our automated solution MassBalancer can digitise and scale all your mass balancing needs. Let us help you in this transition towards sustainability.

Circularise is the leading software platform that provides end-to-end traceability for complex industrial supply chains. We offer two traceability solutions: MassBalancer to automate mass balance bookkeeping and Digital Product Passports for end-to-end batch traceability.

Third-party certifications like RED II biofuels and ISCC PLUS play a crucial role in reinforcing the trustworthiness and integrity of sustainability claims.

.png)