The European Union has ushered in a new era of packaging sustainability and circular economy principles with the landmark Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) — Regulation (EU) 2025/40. Officially published in January 2025, this directly applicable regulation replaces the Packaging Directive 94/62/EC, creating a unified legal framework for all EU Member States.

The PPWR's goals are ambitious and urgent: to make all packaging reusable or recyclable by 2030, drastically reduce environmental and health impacts, and accelerate the transition to a circular economy.

It imposes strict, binding obligations across the entire value chain—from manufacturers and importers to distributors—covering recyclability, mandatory recycled content, reuse systems, harmonised labelling, and packaging minimisation.

This comprehensive guide will break down the PPWR's key rules, critical timelines, and compliance strategies. We will provide a detailed overview of the regulatory timeline, including important deadlines and transition periods. Furthermore, we will offer a special focus on one of the most critical tools for compliance: mass balance accounting, the essential method for tracking and verifying recycled content, particularly from advanced recycling processes.

What is the PPWR and what is it for?

The Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR), formally Regulation (EU) 2025/40, marks a new era for packaging legislation in the European Union. Adopted on 19 December 2024 and published on 22 January 2025, the PPWR replaces the long-standing Directive 94/62/EC on packaging and packaging waste. Unlike a directive, which required each Member State to implement its own national legislation, the PPWR is a regulation. This makes it directly applicable across the EU, creating a uniform legal framework for all packaging placed on the Union market (Article 71; Recital 3).

The shift from a directive to a regulation is one of the most significant changes, intended to harmonise rules across Member States and eliminate internal market barriers caused by fragmented national measures. This means that economic operators — from manufacturers to importers — can now rely on a single, coherent set of rules throughout the EU (Recital 3).

The PPWR is firmly embedded in the EU’s sustainability and circular economy priorities, aligning with:

- The European Green Deal

- The Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), which commits to making all packaging reusable or recyclable by 2030

- The Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability, which addresses the reduction of substances of concern in packaging

The ambitious and comprehensive objectives of the PPWR reflect the EU’s push toward a fully circular economy. At its core, the regulation seeks to harmonise packaging rules across the single market by eliminating national discrepancies that have long created barriers for businesses and undermined efficiency. This ensures that manufacturers, importers, and distributors can rely on one uniform set of packaging requirements throughout the EU.

Equally central is the regulation’s environmental mission. The PPWR is designed to prevent and reduce the negative impacts of packaging on the environment and human health by addressing the entire life cycle of packaging — from design and production to collection and recycling. A pivotal milestone is the commitment to make all packaging either reusable or recyclable by 2030, a step that underpins the EU’s transition to a circular economy.

The regulation also targets the reduction of excessive and unnecessary packaging, prioritising designs that use fewer resources while improving recyclability. For plastics, Europe’s most carbon-intensive packaging material, the PPWR drives the uptake of recycled content, reducing dependence on virgin materials. By cutting material use and fostering circularity, the PPWR contributes directly to EU climate objectives, including the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from packaging production, transport, and waste management.

What is the timeline of implementation for PPWR?

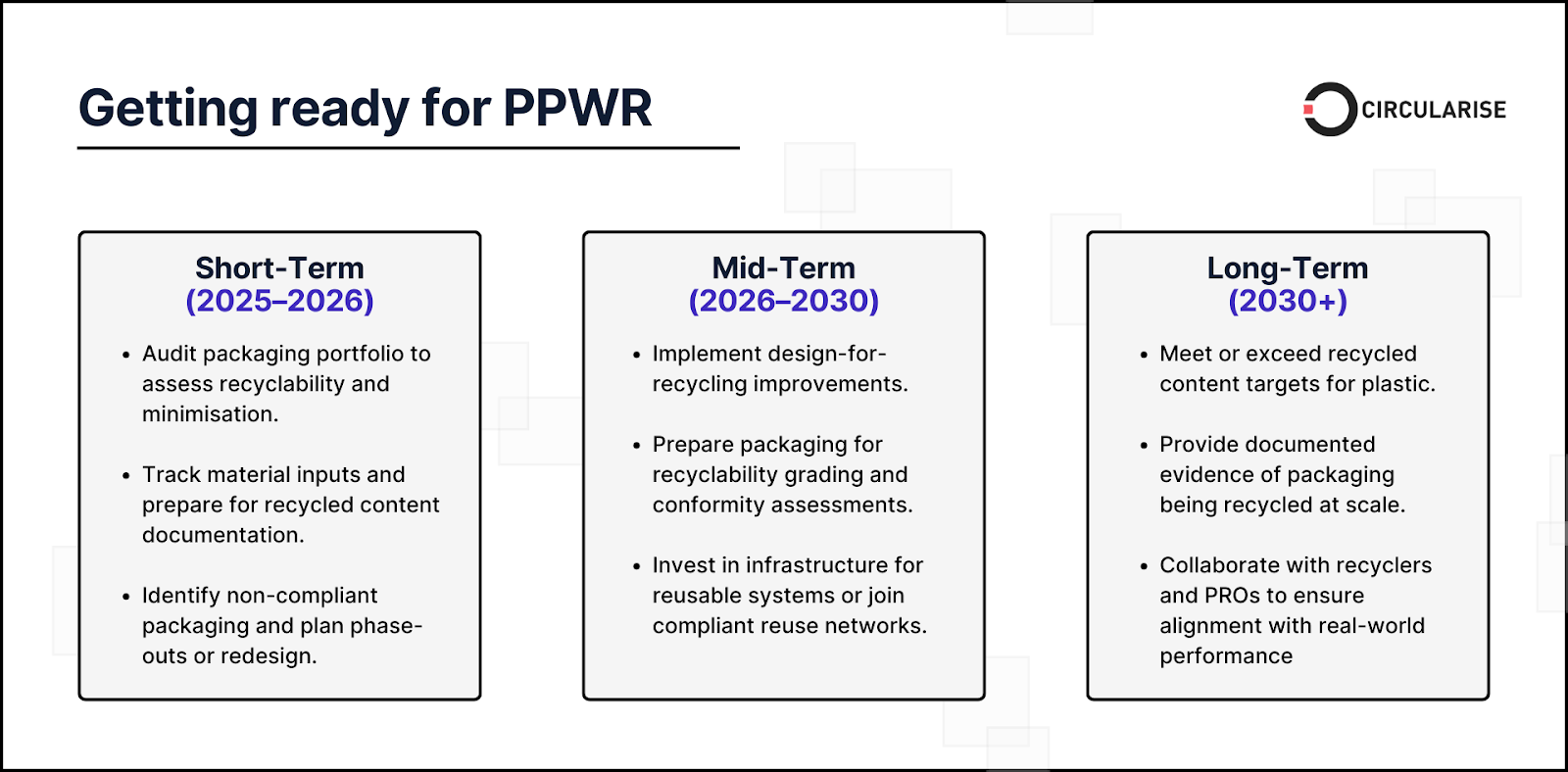

The PPWR phases in its requirements over more than a decade, giving businesses a clear adaptation period. Published in January 2025 and entered into force in February 2025, with general application starting in August 2026. Harmonised labelling is scheduled for 2028‑2029, depending on implementing acts.

From January 2030, the first major obligations take effect. Only packaging with recyclability grades A‑C may be marketed, and minimum recycled content thresholds for plastic packaging apply. By January 2035, recyclability must be demonstrated in practice at scale, and by January 2038, only grades A and B will remain permitted, phasing out of all lower‑performing packaging.

This clear, staged timeline allows companies to audit existing packaging, secure recycled content, develop reuse systems, and align documentation processes well before enforcement escalates. Those that act early will be best positioned to maintain EU market access and show leadership in sustainable packaging.

Who and what does the EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) apply to?

The Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) has a broad and comprehensive scope, ensuring that all forms of packaging used within the European Union are covered. The regulation applies to all packaging placed on the EU market, regardless of the material, function, or whether it is empty or filled with products. This includes:

- Business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) packaging;

- Household, commercial, industrial, e-commerce, and transport packaging;

- Packaging produced within the EU and packaging imported from third countries.

This wide applicability ensures that no packaging escapes the sustainability requirements, closing previous gaps that allowed certain products to avoid regulation.

One of the PPWR’s critical contributions is providing clear and harmonised definitions of packaging categories, which is crucial for legal certainty and uniform enforcement across Member States. The regulation distinguishes:

- Sales packaging (primary): Packaging conceived to constitute a sales unit for the end user or consumer at the point of purchase.

- Grouped packaging (secondary): Packaging designed to group a number of sales units, either to facilitate handling or stocking, or to be sold as a multi-pack.

- Transport packaging (tertiary): Packaging designed to facilitate handling and transport, preventing damage to goods in transit, but excluding containers used for transport by road, rail, air, or sea.

- Service packaging: Packaging filled at the point of sale to allow or facilitate the delivery of goods to the consumer, such as takeaway coffee cups or sandwich bags.

- Composite packaging: Packaging made of different materials which cannot be separated by hand into single-material components.

These definitions are essential because they determine which rules apply to which type of packaging, including recyclability, labelling, reuse, and minimisation requirements.

What qualifies as packaging under PPWR?

The regulation is clear that some items that may seem incidental or secondary still count as packaging under the PPWR. An item is legally considered packaging if it serves to contain, protect, handle, deliver, or present a product, even if small or seemingly insignificant.

For example, sticky labels attached directly to fruit or vegetables are packaging because they present and identify the product. Similarly, collation films, shrink wraps, and overwraps used to group products for sale or transport are treated as packaging because they facilitate handling and distribution.

Other items that often cause confusion are also explicitly classified as packaging. Clothes hangers sold together with garments are packaging, because they present and support the product in a sales context, while CD or DVD spindles sold with discs are packaging because their primary purpose is to group and protect the discs during sale and transport. Cake doilies sold with a cake or paper baking cases filled with pastries are also considered packaging, because they are intended to be used as part of the product’s presentation to the consumer. Even plastic sleeves for cleaned laundry, labels hung on products, and aluminium foil used to wrap food qualify as packaging when they perform a protective or presentational function.

By clearly defining these borderline cases, the PPWR ensures that businesses understand which products trigger packaging obligations and which are exempt. This clarity reduces the risk of misclassification, strengthens compliance with EU law, and supports consistent enforcement across all Member States.

What does not qualify as packaging under PPWR?

Equally important, the PPWR takes the opportunity to clarify which items do not qualify as packaging, resolving ambiguities that existed under the previous directive. Items that are sold empty as products in their own right are not considered packaging.

For example, tool boxes, printer cartridges, sausage casing skins, and clothes hangers sold separately are all treated as products rather than packaging. The same applies to empty CD spindles intended for storage, mechanical querns integrated in refillable recipients such as refillable pepper mills, plant pots and seed trays used in production or sold together with the plant, wrapping paper sold separately, and paper baking cases or cake doilies sold without a cake. Refer to Annex 2 for a comprehensive list of items that do not constitute as packaging.

The regulation also exempts items that are integral to a product’s lifetime and are used, consumed, or disposed of together with that product. A familiar example is the wax layer around cheese or a sausage casing, which is part of the product rather than a separate packaging component. Similarly, plant pots or seed trays that are used solely in production and not intended for sale together with the plant, also fall outside the definition of packaging.

This distinction means that only items that perform a packaging function for a product are regulated under the PPWR. Everything else—like an empty toolbox or refillable pepper mill—remains a product in its own right and is outside the scope of packaging obligations. By providing these explicit examples, the regulation offers legal certainty to businesses and ensures consistent classification and enforcement across all EU Member States.

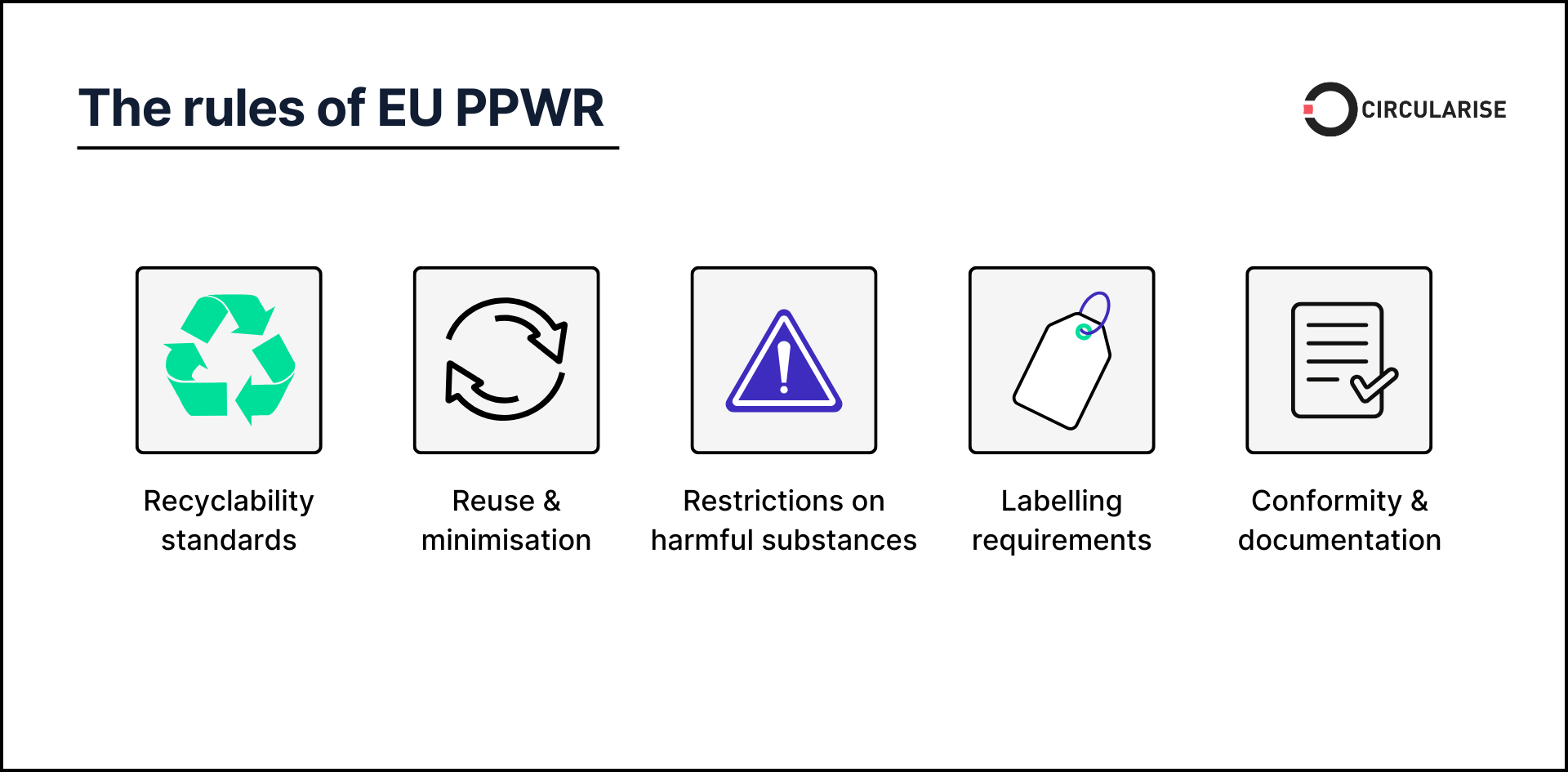

What are the main rules of the EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) that businesses need to know?

The PPWR introduces a comprehensive framework to make all packaging in the EU market recyclable, reusable, and increasingly circular. Its binding rules can be broken down into several key pillars, supported by a clear phased timeline.

Recyclability standards

A cornerstone of the PPWR is its recyclability framework. Every piece of packaging will be assessed and assigned a recyclability performance grade ranging from A to E, based on three key factors: design‑for‑recycling characteristics, compatibility with collection and sorting systems, and actual recycling performance.

From January 2030, only grades A, B, or C may be marketed in the EU, while lower grades will be banned. This threshold tightens in January 2038, when only grades A and B will remain permissible, completing the phase‑out of grade C.

The regulation goes beyond theoretical recyclability. By 2035, packaging must be “recyclable in practice and at scale”, meaning it must be collected, sorted, and processed through existing industrial recycling infrastructure across the EU — not just recyclable in laboratory or pilot conditions. In other words, packaging that is technically recyclable but lacks widespread collection and sorting — for example, certain multilayer plastics or black PET trays that optical sorters cannot detect — will not qualify as recyclable at scale.

Demonstrating recyclability at scale will require audited data from Member State collection systems, EPR schemes, or industrial recycling facilities to prove that the material enters a functioning recycling loop. This provision ensures that packaging which cannot realistically be recycled into usable secondary materials will be phased out of the EU market.

The PPWR also introduces mandatory recycled content thresholds for plastic packaging, effective from 2030. Minimum percentages of post‑consumer recycled content must be achieved, calculated as an annual average per manufacturing plant and per packaging type. Contact‑sensitive applications, such as infant food and medical packaging, are exempt to ensure safety.

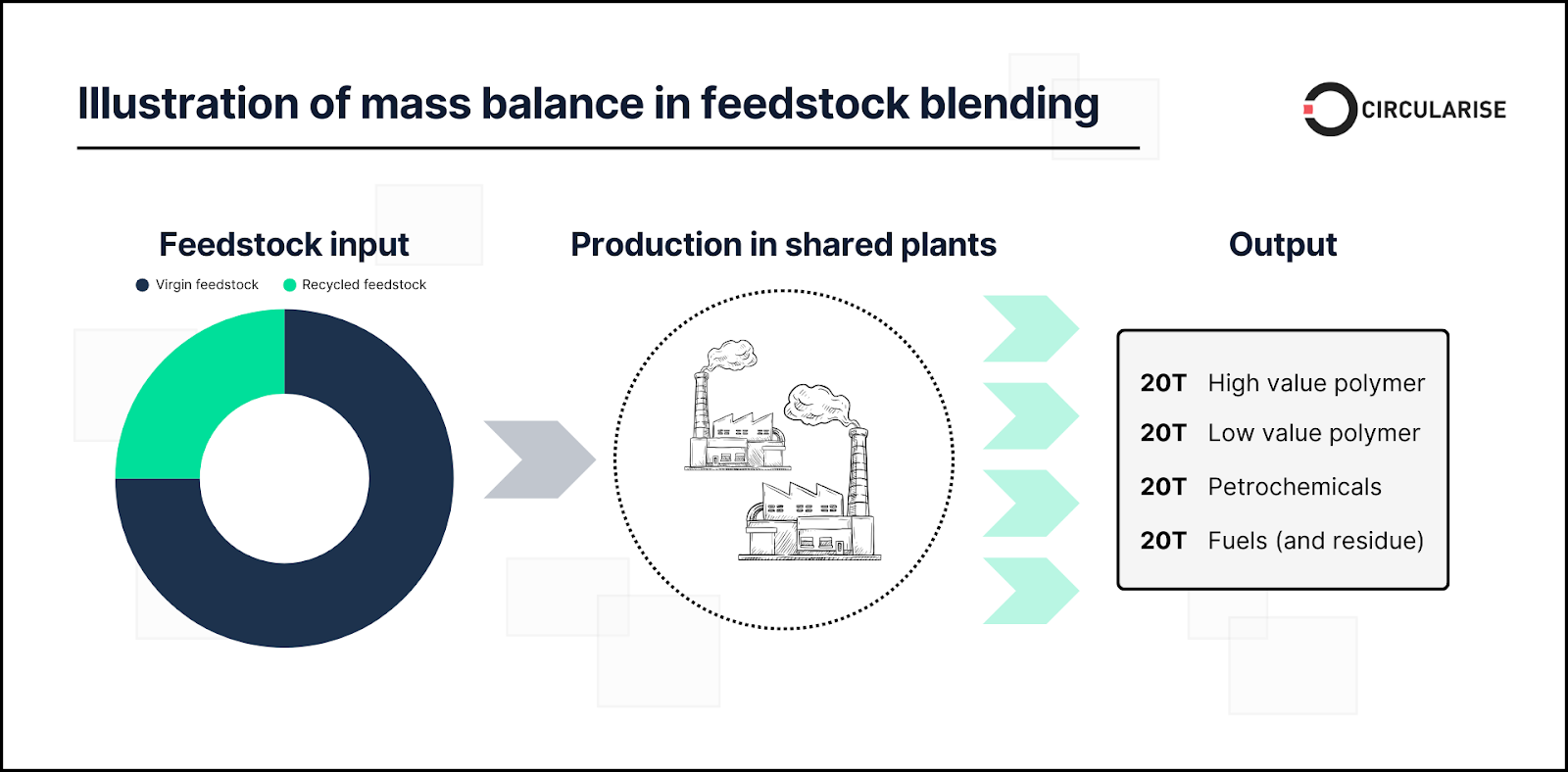

To accommodate chemical recycling, the regulation allows mass balance accounting under strict traceability and auditing rules, enabling companies to claim recycled content based on input/output allocation, even if the recycled molecules are chemically indistinguishable from virgin feedstock. In addition, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) fees will be modulated according to recycled content levels, rewarding higher use of circular materials.

Reuse and minimisation

Reuse and minimisation are equally critical. Packaging must be designed for reuse whenever feasible, capable of a minimum number of rotations within a formal reuse system that includes collection, cleaning, and redistribution. Sector‑specific reuse targets will gradually apply to take‑away food and beverage packaging, retail transport packaging, and large‑scale logistics.

To tackle over‑packaging, the regulation bans false bottoms, double walls, excessive void space, and purely decorative bulk, emphasising fit‑for‑purpose design that uses only the material necessary to protect and present the product.

Restrictions on harmful substances and chemicals

On chemical safety, the PPWR aligns with the EU’s REACH, CLP, and Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability, imposing restrictions on lead, cadmium, mercury, and hexavalent chromium, as well as PFAS in food‑contact applications and a pending phase‑out of bisphenol A (BPA) in plastics. These limits apply to both virgin and recycled materials, preventing toxic substances from recirculating in the economy.

Labelling requirements

To support consumer understanding and waste system efficiency, the PPWR introduces harmonised EU‑wide labelling. By 2028–2029, all packaging must bear pictogram‑based labels showing the material type and disposal method, aligned with matching symbols on waste bins.

Many packages will also include QR codes or digital markers providing material composition, recyclability, reusability, and return or collection instructions. Reusable packaging must clearly indicate its reusability and how to return it, supporting the growth of take‑back and refill systems.

Conformity & documentation

Finally, the regulation requires rigorous conformity assessment and documentation. Manufacturers and importers must verify that packaging and all its components — lids, liners, and labels — comply with the PPWR, maintain technical files and Declarations of Conformity for 5‑10 years, and ensure traceability through batch numbers, barcodes, or QR codes. This documentation enables market surveillance authorities to verify compliance efficiently and take action where necessary.

Circularise is the leading software platform that provides end-to-end traceability for complex industrial supply chains. We offer two traceability solutions: MassBalancer to automate mass balance bookkeeping and Digital Product Passports for end-to-end batch traceability.

We make mass balance accounting easy. Automate calculations, ensure audit-proof documentation, and secure your market access.

.png)